(1).jpg)

In Wonder of Borrowdale

(Photos after text)

Cumbria, and the Lake District, are among my favourite places, and as hundreds of my past posts have shown, I’ve spent a lot of time here. While both the county and national park have existed for less than a century, the history of this land is incredibly deep and rich. From 300-million-year-old fossils to cave men, ancient sheep breeds, Elizabethan miners, and even Swallows and Amazons, it boasts countless stories. On top of this, Cumbria is astonishingly biodiverse. I’ll always mourn the decline of natural high-altitude tree lines and alpine grasslands free of sheep grazing, but I can’t deny the thrill of lying beneath waterlilies in Derwent Water and watching pike lying in wait for ambush, searching for pyramidal bugle flowers in the Kentmere mountain coves, or spotting red squirrels and pied flycatchers among mossy oak forests. There are seabirds at St Bees, and green isopods among the seagrass of Walney, all reminders of the land’s varied natural wonders.

One part of this grand and ancient land has always captured my heart above all others: a land of high peaks and green rainforests, clear crystal waters and murky deep mines. While that description could fit many places around the Lake District, Borrowdale stands out in particular. It is a charismatic land, rich in both ancient history and natural beauty, with a unique spirit that always draws me in. Specifically, I’m referring to the watershed catchment of Derwent Water, which extends all the way up to the highest peak—Scafell Pike (though technically, the neighbouring Great End marks the margin of the catchment, and Scafell lies just outside, the vibe remains unmistakable).

I’ve hiked here many a time, often venturing into hidden forested locations around the valley. I’ve wild-camped on mountain plateaus, crossed centuries-old packhorse bridges, paddleboarded up the Derwent River, and swum in the high alpine Styhead Tarn. I’ve ghyll-scrambled Cat Gill from its confluence with the lake, climbing waterfalls and trudging through bogs in the fells until reaching its source. I’ve climbed to the top of the famous Bowder Stone (without using the stepladder), and scrambled up the Hanging Stone of Base Brown. Borrowdale is also where I based my dissertation, studying the impact of canopy cover on moss and liverwort species growing on tree trunks in the temperate rainforest. I've loved discovering rare species, such as alpine enchanter's nightshade and touch-me-not balsam, in its woods. I've explored parts of this valley visited by thousands annually, and other parts I’m sure nobody but me has set eyes on for centuries. And wherever I go in Borrowdale, or whatever story I’m reading—whether it’s about brook lamprey breeding sites or The Wolf Man of Eagle Crag—I’m always struck with a profound sense of wonder for this gorgeous mountain valley.

This land, steeped in history, legend, and wildlife, is, I find, best represented by the mountain slopes west of the small farmstead of Seathwaite. Here, on the furthest edges of Seatoller Wood, which gradually gives way to upland pastureland with ever-sparser tree cover, stand three ancient yew trees. They’ve been here since around the 500s AD, not long after the Romans abandoned the isles, and the local people likely still spoke the extinct Cumbric Brithonic language, a relative of modern Welsh. That places them over 1,500 years old! These trees have witnessed the rise and fall of the kingdoms of Rheged and Strathclyde, lived through ages of mythical people such as Dunmail, the last King of Cumbria, and perhaps even King Arthur. They’ve watched as the English crown hired workers from overseas to mine deep into the mountainsides, and stood strong as peak baggers rush past in an effort to complete each peak listed by Alfred Wainwright. People have come and gone, nearby trees and whole forests have been felled and regrown. Waterfalls have been diverted; rare fish transported high into the mountains. If these trees could speak, their memory would tell a million marvellous tales.

Sadly, the ancient Borrowdale Yews cannot speak to us. Locked in an eternal muteness, their only voice is the faintest whisper among the needles on their branches in the mountain breezes. However, it seems the mountainside into which they are anchored has learned to write for them. Before the 16th century, writing was an expensive skill to acquire. Ink had to be prepared, or wax tablets made. Some lead or silver pencils could mark paper, but there was little to bring writing to a wider scale for practice in schools. That was, until the early 1500s. The story goes that a tree was uprooted in a storm upslope from the Borrowdale Yews, and local farmers found an unusual substance beneath. This mineral had been known to humanity before, but never in such pure form. For the locals, it was invaluable for marking sheep to denote ownership.

Wad—that’s what they called this new rock. It would later be known as plumbago when scientists mistakenly identified it as a form of lead. Over time, the mineral was found to have a number of uses, but it was Queen Elizabeth I who recognised its value for mining at a commercial scale. This led to the creation of a large quarry near the top of the steep slope, eventually evolving into a maze-like network of tunnels as miners sought the confusing veins, or 'pipes,' of wad deep in the mountainside. The quarry remained in use until the 20th century. Wad turned out to have many uses, but perhaps the most significant early on was its suitability for making cannonball moulds, highly coveted throughout Europe. The price of wad skyrocketed, and numerous tales of smugglers attempting to steal from the mines are now embedded in the land’s lore. Amidst all the chaos, however, another invention was born—one that, while perhaps initially sidelined, has now undeniably become the most important invention to have come from Borrowdale: the graphite pencil. That’s right—wad is graphite, and it was here that the modern pencil seems to have been invented. A purer form of this remarkable mineral has never been found outside of Borrowdale, though sadly this didn’t save the industry here as it was discovered that the same effect could be produced by crushing lower quality graphite forms and mixing them with a large proportion of clay, destroying the previously lucrative industry.

In February 2022, I set out to collect some original Borrowdale graphite. Passing the Borrowdale Yews, I found several fallen twigs from recent storms and pocketed one before continuing up into the fells to the old slag heaps of the wad mines. There, in the morning sun that had just swept Glaramara’s shadow down into the valley, small rocks glittered among the grey—shiny silver pieces that looked as smooth as though they’d been melted, their purity unmistakable: pure graphite.

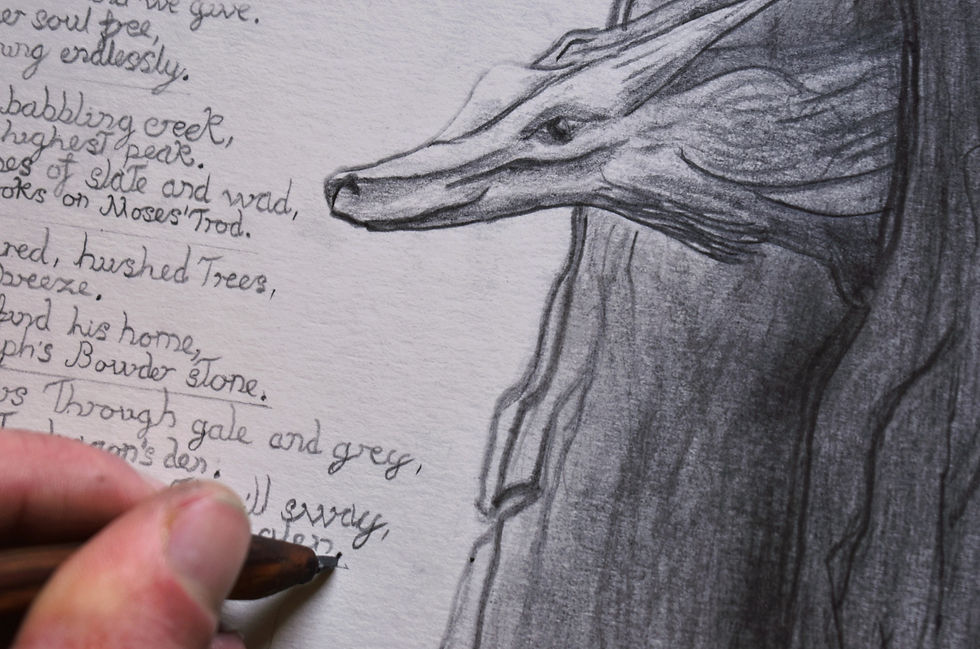

With these collected, I knew exactly what to do and set about re-inventing the pencil. I can’t exactly brag about my attempts—mostly involving just a small replaceable nib of graphite inserted into the ends of carved wood rather than crafting a full shaft through the wood that would allow for sharpening, as in a traditional pencil. But I’ve kept plenty of spare pieces for future attempts. One pencil in particular I’d never want to sharpen anyway, due to its special wood. The twig I had found fallen from the Borrowdale Yews, which, when the rotten outer layer was carved away, revealed a beautiful orange wood beneath. (Note: be careful using yew wood, as it is toxic after all.) One of the old trees had grown this twig with a number of smaller branches along its length, which, over time, had eroded into sharp spikes that reminded me of the horns on a dragon’s head. So that is what I made—a Borrowdale yew pencil, with Borrowdale wad, and a dragon-shaped pencil holder. From here, I began making a sketch of the largest of the yews, its ancient, gnarly, and hollow trunk becoming the feature of the artwork. I used my yew pencil for some parts, but also other pencils I’d made, and I admittedly largely just used small rocks of graphite that I would occasionally sharpen a little point with using a wood carving knife.

As I worked, a huge blank space revealed itself in the sketch, and I began to wonder about adding in a poem about the Borrowdale Yews, written by the famous Cumbrian poet William Wordsworth:

‘There is a Yew-tree, pride of Lorton Vale,

Which to this day stands single, in the midst

Of its own darkness, as it stood of yore:

Not loathe to furnish weapons for the Bands

Of Umfraville or Percy ere they marched

To Scotland's heaths; or those that crossed the sea

And drew their sounding bows at Azincour,

Perhaps at earlier Crecy, or Poictiers.

Of vast circumference and gloom profound

This solitary Tree! -a living thing

Produced too slowly ever to decay;

Of form and aspect too magnificent

To be destroyed. But worthier still of note

Are those fraternal Four of Borrowdale,

Joined in one solemn and capacious grove;

Huge trunks! -and each particular trunk a growth

Of intertwisted fibres serpentine

Up-coiling, and inveteratley convolved, -

Nor uninformed with Fantasy, and looks

That threaten the profane; -a pillared shade,

Upon whose grassless floor of red-brown hue,

By sheddings from the pining umbrage tinged

Perennially -beneath whose sable roof

Of boughs, as if for festal purpose decked

With unrejoicing berries -ghostly Shapes

May meet at noontide: Fear and trembling Hope,

Silence and Foresight, Death the Skeleton

And Time the Shadow; there to celebrate,

As in a natural temple scattered o'er

With altars undisturbed of mossy stone,

United worship; or in mute repose

To lie, and listen to the mountain flood

Murmuring from Glaramara's inmost caves.’

However, I found Wordsworth's poem uninspiring (no offense to him). Not to mention, since he wrote it, one of 'Those Fraternal Four' had been killed in a storm in the 1860s. I decided instead to attempt my own poem—one that would incorporate the Borrowdale Yews, their fallen companion, wad, and the majesty of Borrowdale. Looking at my dragon pencil holder, grown from the ancient yews themselves, an idea began to form. The fallen tree still lived among her fellow yews in spirit—in the form of a small wood dragon. And with her spirit set free from its wooden home, she could now remember and reminisce about the years the trees have withstood and the people they’ve seen come and go in the ever-changing landscape.

From this, my poem was born—The Borrowdale Yews.

A timeless place, three ancient yew,

The land surrounding these yews has undergone many transformations throughout the centuries, but the small grove where they stand has remained untouched by human progress. Millennia of change—woodlands felled, mills built, mountains mined, and even the Vikings arriving—have come and gone, yet the yew trees persist. These trees symbolize an enduring resistance to time and death, their presence immortal and timeless, surviving all forces that have reshaped the world around them.

In emerald umber dwell.

The yews’ canopies, evergreens that retain their glossy green leaves throughout the seasons, contrast with the earthy orange hues of their trunks (umber) and the shade they cast beneath their boughs (umbre). This deep, evergreen shelter, never fully penetrated by the harsh light of summer or winter, creates a magical atmosphere. It's a world of undisturbed calm.

Four kin of old this grove once knew,

There were once four yew trees in this grove, a fraternity that Wordsworth poetically recognized as "Those Fraternal Four." Tragically, a storm in 1866 claimed one of these trees, leaving only three standing to carry on the legacy.

Since Rheged rose and Dunmail fell.

The Borrowdale Yews are thought to be around 1,500 years old. This places their early growth around the same century as that of Urien ap Cynfarch Oer, among the most famous kings of Rheged, an early Celtic kingdom of post-Roman Britain that is considered in old Welsh sources to be part of the Hen Ogledd (Old North). The exact extents of Rheged throughout history isn’t known but much of modern Cumbria is typically considered largely within the kingdom. Rheged’s history technically goes back further than this, right up to the time of Roman Britain’s decline in the 400s AD. Of course, the history of Celtic rule in the area gave way over time to England, and this is recounted in the tale of King Dunmail, the legendary King of Cumbria who fell to the joint forces of King Edmund and King Malcolm in the Lake District. It may be a mythical telling of the fall of the Kingdom of Strathclyde under King Dyfnwal, which included and later even became referred to as the Kingdom of Cumbria after the fall of Rheged to Northumbria and then waning of Northumbria’s power by the Viking incursions until its inclusion into Strathclyde. In this way, these trees watched the regrowth of Celtic power after the retreat of the Romans, all the way through to its demise to England centuries later. Through it all, the yews have remained, observing the ebb and flow of history.

Yet unseen hides the fallen fourth,

Though the fourth yew tree has physically fallen, its memory persists in the grove and in the collective consciousness. It is a spirit that lingers, hidden but ever-present, in the stories told of the grove, unseeable yet felt, like a whispered memory.

A yewen spirit wakes.

The spirit of the fallen yew awakens as we recall its memory, brought to life through the act of storytelling. In this mythical sense, the yew's spirit is reanimated, rising from the past as a dragon-like entity, reclaiming its place in the mythic landscape.

Serpentine wood in hidden swarth,

The yew tree’s wood, twisted and gnarled like the coils of a serpent, forms the essence of the spirit now reanimated. Like a dragon made of wood, the spirit slithers through the undergrowth, hidden beneath the grass (swarth), taking on a serpentine form. The imagery of the word ‘serpentine’, as well as being an apt description and linking to Wordsworth’s own poem on the topic, connects the twisted, serpent-like branches with the soft green mineral "serpentine," evoking the arriving presence of Celtic Christianity in the area due to this famed mineral’s presence as ‘St Columba’s Tears’ on the Isle of Iona where he first landed and began the spread of Christianity down towards Cumbria, as well as early manuscript traditions like the Book of Kells. This rich layering of meaning adds depth to the spirit’s connection to both nature and history.

Twisting through elder bough she snakes.

The dragon slithers and winds through the thick boughs of the remaining trees, particularly the largest, which is hollowed out and home to countless other creatures. These trees, now likened to sisters, become the dragon’s siblings, as it moves among them like a living entity intertwined with the forest. This is in conflict with Wordsworth’s reference to them as fraternal (brothers) but he did also mention the growth of berries on these trees. Yew trees are dioecious – some trees only produce male pollen structures, and others only produce the seeds to take that pollen and form berries. In this way, yew trees can only be male and female so if Wordsworth was correct about the berries, he misgendered them. There is also an additional and little-understood feature of ancient yews whereby some can start to exhibit monoecious (hermaphroditic) tendencies, or even switch sex altogether. When I visited the yews in February I saw no reproductive structures, but not long later I saw other yew trees that had clear pollen structures, showing they were male, so unless I was a little to early for that in Borrowdale it seems they are female trees.

Dragon, lindworm, and Beithir-nimh,

These names for mythical serpents—dragon, lindworm (a limbless, snake-like dragon), and Beithir-nimh (a Gaelic term for a deadly, poisonous serpent)—capture the essence of the yew spirit in its dragon form. 'mh' makes a 'v' sound in Scottish Gaelic, while the 't' here is silent.

So many names her kind we give.

Throughout history and across cultures, serpent-like creatures have carried many names, each reflecting their significance in mythology. These names tie the yew spirit to a vast, shared cultural heritage, one that has shaped human belief systems and stories for millennia. The spirit of the yew is part of this broader tapestry, endlessly shifting and adapting in human lore.

Bark to scale, her soul free,

As the yew tree’s spirit transforms from a solid, rooted form to something free and fluid, the bark gives way to interlocking scales. The once rigid and rooted nature of the tree becomes the fluid, serpentine form of the dragon. This transformation reflects the spirit’s release from the constraints of the physical world, able to reminisce about the stories she witnessed as a tree.

Memory reaching endlessly.

The yew’s spirit is a vessel of memory, stretching across time. It holds within it the stories of Borrowdale, a living record of the valley’s long history. Through the yew’s spirit, the memories of centuries past are kept alive, and this continuity will persist long into the future, carried forward by the surviving yews, who will continue to witness and remember.

Darkest wood, babbling creek,

The memory of the yew tree reaches back to the deep, shadowy woods of Borrowdale, with their lush, temperate rainforests and steep slopes, some of which still survive today and were recently proclaimed a nature reserve. These woods, intersected by streams and waterfalls flowing down from the mountains, offer a natural beauty I find few other environments capture.

Alpine moors, highest peak.

In contrast to the dense woodlands, Borrowdale is known for its rugged upland moors and towering mountain peaks. The landscape here is vast and seemingly untamed, where the air is thin and the views stretch across distant valleys. In reality this landscape is criss-crossed with walls and paths some centuries old, including man-made sites predating even these yew trees by millennia, and a tradition of sheep grazing that has made an artificial yet beautiful habitat. Scafell Pike, the highest peak in England, casts its shadow over the yews, anchoring them in the geography of the land.

Labyrinth mines of slate and wad,

The mining history of Borrowdale is legendary. Slate and graphite (wad) have been extracted from its rich seams for centuries, shaping the local economy and culture. Honnister slate mine works even to this day, and the wad mines in particular are labyrinthine, confusing and winding, reflecting the complexity and value of this resources. The yews have witnessed the extraction of these materials, their ancient presence a silent observer of human industry.

Kinsmen and crooks on Moses’ Trod.

The miners, both local and foreign, became part of the community, bound by the hardships of life in the valley. Some, like Moses Rigg, are remembered in local legend for their illicit activities—smuggling wad and brewing moonshine whisky. The "Moses’ Trod" route is named for him, a treacherous path he is said to have used to move goods between Borrowdale and the coast via Wasdale.

Stories murmured, hushed trees,

The yews have seen much, but their stories are not told loudly. Instead, their history is whispered through the rustling of their leaves, murmured in the quiet moments between the wind and the branches. These ancient trees, holding the memory of the valley, cannot truly offer their stories to us, but in learning and exploring, for those willing, a new level of life and wonder can be found in the landscape.

Forest needles in breeze.

The yew trees’ needle-like leaves whisper in the wind, their rustling a subtle reminder of the past. Each breeze through the branches carries the murmur of ancient stories, faint and elusive, like voices from a forgotten time.

She’s seen old Dalton find his home,

Millican Dalton, a figure of quiet eccentricity, found his home near the ancient yews, choosing a simple life in a cave below Castle Crag. Despite his isolation, he was an educated man and connected to the wider world through letters and his adventures. The self-crowned ‘Professor of Adventure’ inspired many people on the excursions he led, including trips abroad before returning to his humble cave. His life, though humble, was rich with curiosity, and he is now part of the folklore of Borrowdale.

Heard tale of Joseph’s Bowder Stone.

Joseph Pocklington is another enigmatic Borrowdale character. A wealthy man, he lived for a time on Derwent Isle in Derwent Water, building a druidical stone circle and organising annual regattas to be organised whereby Keswick locals would attempt to siege his island which he fortified well. He also later had a mansion built further south along the road to Borrowdale, diverting a nearby waterfall in order to improve the way it looked. Most famously, he managed to turn the huge fallen boulder in Borrowdale, known as the Bowder Stone, into a tourist attraction, even hiring an old lady to live full-time in a nearby cottage and charge people to climb the steps he had put in up to the top of the boulder.

These ancient sisters through gale and grey,

The yew trees have stood through countless storms, their resilience a testament to the endurance of nature itself. Despite the harsh weather, Borrowdale being recorded as the rainiest place in England, the yews remain steadfast, symbols of endurance and strength through time.

Heartwood hewn to dragon’s den.

The hollowed-out heartwood of the largest yew forms the dragon’s den, a metaphorical home for the spirit of the fallen yew. The dead heartwood has rotted away, but it still remains at the heart of the tree, a sheltered space, caring and nurturing to many small organisms that call it home while the living sapwood around the sides maintains the canopy above.

For a thousand years yet on they’ll sway,

The yews have lived for over a millennium, and though some may fall to time, the hope is that these trees will continue to sway for thousands more years, carrying on the legacy of their ancient line. While 1,500 years truly is ancient, some other British yews are among the oldest trees in Europe, estimated to reach even 5,000 years old.

A home and hollow within the glen.

The small grove of yews, tucked into the glen of Borrowdale, is a place of peace and refuge. It is a sanctuary, a home for the trees and those who come to experience the quiet magic of the valley. The hollowed trunks and shady glen provide a sense of connection that I feel deeply throughout Borrowdale.

I hope others can enjoy this project as much as I did. Borrowdale will always hold a special place in my heart.

A timeless place, three ancient yew,

In emerald umber dwell.

Four kin of old this grove once knew,

Since Rheged rose and Dunmail fell.

Yet unseen hides the fallen fourth,

A yewen spirit wakes.

Serpentine wood in hidden swarth,

Twisting through elder bough she snakes.

Dragon, lindworm, and Beithir-nimh,

So many names her kind we give.

Bark to scale, her soul free,

Memory reaching endlessly.

Darkest wood, babbling creek,

Alpine moors, highest peak.

Labyrinth mines of slate and wad,

Kinsmen and crooks on Moses’ Trod.

Stories murmured, hushed trees,

Forest needles in breeze.

She’s seen old Dalton find his home,

Heard tale of Joseph’s Bowder Stone.

These ancient sisters through gale and grey,

Heartwood hewn to dragon’s den.

For a thousand years yet on they’ll sway,

A home and hollow within the glen.

_JPG.jpg)

_JPG.jpg)

_JPG.jpg)

%20(2)_JPG.jpg)

_JPG.jpg)

_JPG.jpg)

_JPG.jpg)

_JPG.jpg)

.jpg)